Urban Design focuses on the creation of spaces for us to live, dwell, congregate, celebrate and share, not only with other people but also with all the other living communities whom we share the territory with.

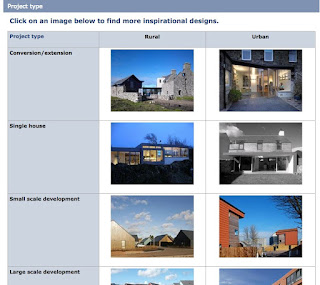

The word urban presupposes that the discipline only concerns itself with matters that exist within the urban realm but that is not necessarily the case. Urban Design is a broad creative and experimental field that contributes to meaningful and engaging forms for us, humans, to exist in the world, whether in urban or rural environments. Or that should be the case. Throughout history, examples of good and bad urban design ideas, solutions and proposals abound, most of which are far from unanimous.

Due to the fact that Urban Design helps us defining such essential characteristics of human settlements, it cannot exist without controversies from time to time. Perhaps the most famous and impactful controversies have happened in big cities, not because they are more important than smaller cities, towns, villages or even the countryside, but precisely because they congregate more people.

Cities are the most complex human settlements on the planet and considered to many people as the most extraordinary human invention of all. No other species known to us was ever able to create such dynamic systems. Certainly, life has invented many ways to build complexity and resilience that involve communities living together for a greater good, but no other gets even close to the city.

Cities have also proven to be an extremely successful invention. Not only are they a trans-civilisational idea—the very notion of civilisation implies the existence of a civitas, or city, as the epicentre—repeated, reinvented and improved time after time, but they are also becoming progressively more dominant territorially, economically, socially, culturally, philosophically and even digitally.

According to the last UN-Habitat report, in the beginning of the 20th century, close to 15% of the world’s population lived in cities; in the beginning of the 21st century that number was close to 50%; and it is expected that from 2000 until 2030 virtually all of the population growth will happen in urban areas. By 2015 estimates indicate that there will be twenty-three mega-cities (six of them with over 20 million people) (Perlman, 2005). Because of real-estate demands and most political decisions coming from institutions of power, this massive migration of humans (mainly composed by people trying to escape from poverty) will not be settling in city centres, but rather in those dynamic edge-territories where rules are weaker, most of the times – the formal city gives way to the informal city (Brand, 2009) (Neuwirth, 2005).

Although cities are getting bigger every day, our planet is always one and the same: it does not enlarge its mass, its volume or its surface. This means that every time a city gets slightly bigger or denser, we are transforming the world. In order to build bigger and denser cities something is got to give eventually. If what we need, sometimes even wish, is to bring more people into the city perimeters, then what we end up loosing is, most of the time, the value of the landscape. It is not unusual that a city looses its fertile ground (and therefore productivity), or varieties of animals and plants (and therefore diversity), or unpolluted waters. These, among some others, are the so-called ecosservices that can be both qualified and quantified if commoditised. But landscape does not only translate into services. It is something far more complex, that includes scale and size, space and time, symbolic value, ethic and aesthetic value, expansion and enclosure, protection, amenities, etc. An interesting question naturally emerges: is the loss of landscape value implicit in the creation of cities? Or has it been happening as an unfortunate situation, given the lack of quality in planning, policymaking and nature preservation and enhancement? And, more important than that, are there alternative ways of making city?

Although in most city centres today we face an inevitable loss of landscape in its many intrinsic dimensions and are left with the apparently inevitable condition of infertility, the answer to this question is far richer that it may seem. It is also perhaps one of the most significant questions we will deal with along this semester.

The quest for the value of the landscape within the city opens up yet another potentially interesting question for us. What makes the landscape architect as one of the perfect candidates to develop urban design proposals? Why should we believe that the role of landscape architecture is vital for the city development?

In order to succinctly answer that question it is first important to notice that Urban Design is never a one-man show. The proposals are developed with robust inter- and multi-disciplinary teams with many specialties that interweave their design and research methods. Architecture, urban design, urban planning, many types of engineering, hydrology, sociology, economy, sometimes even ecology or biology and, of course, landscape architecture. Among these, landscape architecture is the only discipline concerned with the landscape per se, that is, with the value, the role and the performance of the landscape at a wide range of scales, from the tiny mycorrhizae that live in the tree roots, to the enormous regional landscape-infrastructural projects. It is also one of the few (perhaps along with planning) with the ability to integrate the core scales of urban design within the bigger or smaller scales with which it necessarily relates to.

Second, the fact that the growth of our cities seems to have implied a consistent loss of landscape and that we live in a world with finite resources many of which are ensured and maintained by the landscape itself, gives a definite and prominent role to landscape architecture in the creation and transformation of our world.

From the point of view of many theoreticians, cities evolve and operate like organisms. They are born, they grow until they reach their maximum capacity, they have a period of maturation and then they eventually decline. In the meantime they live under rigorous metabolic processes that can and should be compared to our own physiologic processes: eating, sleeping, breathing, reproducing, etc. In this course, you should pay attention to these processes and learn to design with them, for they are perhaps the best hints one may have when making crucial decisions.

Reading, interpreting, representing and eventually even manipulating these metabolic processes requires a special attention to the urban systems that produce them. It is not simply a matter of reading the house, the street, the square or the neighbourhood. It is a matter of understanding them as a network operating at different scales, with different momenta, and interconnected with other equally fundamental networks (water, vegetation, gas, traffic, telephone, internet and so on). It is a matter of understanding the urban qualities and contemporary conditions of these metabolisms.

Urbanism///Metabolism is the topic of this year’s Urban Design & Housing. All the aforementioned structural and circumstantial characteristics of the contemporary cities can be easily observed in Edinburgh, which will be taken as our urban lab in the first part of the semester. Due to the city’s moderate size and scale and its historical good practices in urban planning and design (though sometimes disregarded), one may need to look a bit deeper, but as you will observe, common problems – such as gentrification, real-estate speculation, lack of social housing, lack of planning in the peripheries, etc. – not only exist, but also are responsible for some of the most vibrant areas in the contemporary city.

Tiago Torres-Campos